A simple K4 example

In this post, I will present a very simple K4 example that you can follow along and run yourself.

The example is a simple guessing game. The program picks a random number between 1 and 100. The player guesses the number then the computer tells them if its too high, too low or just right. It also counts how many guesses you made to get your answer.

Pretty basic. This example though gives us insight into many basic K4 concepts including:

Introducing file inclusion and our “stdext.k4” collection of useful words

Use of a vocabulary to separate our program from the built-in vocabulary

Random number generation and some modulo arithmetic

Some user input and validation

Lets get started!

(*

Guessing game in K4

Jonathan Masters

Bored Owl Pty Ltd

Nov 2025

*)

." stdext.k4" include

clear

These first lines are straightforward. Some always has to take credit :)! Then we include the file named “stdext.k4”. To do this we need strings and a word that can do this for us. Strings in K4 begin with the word:

.”

There is always a space after the word (after any word - that’s what delimits it), then we follow with the actual string text. When K4 is taking the string in, the occurence of a quotes (“) ends the string. So the input .” stdext.k4” creates a string, the address of which is put onto the stack. The next word “include” expects the address of a string to be on the stack. It then opens a file by that name and reads its contents. This happens to be the K4 code:

(*

K4 Standard Extensions (non-built-in)

(use: '." stdext.k4" include' to read into your dictionary

Author: Jonathan Masters

(C) 2025 Bored Owl Pty Ltd

*)

#

# <n> historic : print the nth last item in the history

#

: historic $cmd $> . ;

#

# .r, .xr, ..r, ..xr - prints with returns

#

: nl 10 emit ;

: .r . nl ;

: .xr .x nl ;

: ..r .. nl ;

: ..xr ..x nl ;

# tab : emits a tab character

: tab 9 emit ;

I won’t explain this code, suffice it to say that it provides us with some “utility” words that are useful in lots of programs. It is documented in an appendix of the K4 manual. We are going to use the word ‘.r’ that prints the top of the stack with a new line appended.

After we include this code we clear the stack with the built-in word ‘clear’. Its a good idea to keep the stack clean and neat.

So we move on to the next section of the code. Before we do, we need to explain the concept of “vocabularies”. In the beginning, K4 gave us “words” - about 200 builtin words at last count. These are in the “dictionary”. If you want to see them all, try the K4 expression:

4 words

This will give you a listing of all the words in the dictionary. More precisely, it will give a list of all the words in the current vocabulary in the dictionary. A vocabulary is a subset of the dictionary that is prefixed with a vocabulary name. When K4 starts up, only the default dictionary with all its built-in words exists. Including ‘stdext.k4’ defines a few more in this default space.

If we pose the question: “what happens if I define a new word with the same name as one that already exists?” the answer is not always great. The answer is that the most recently defined version of any word is the one that will be found and executed. This can be useful if you need to override a built-in. It can also cause bugs and problems if you didn’t know you did it - we’ll see this a bit further on.

To alleviate the problem of unintentionally overwriting words and not being able to use word names for our own purposes, K4 gives us “vocabularies”. We can define a new vocabulary and give it a name. Then we can make that vocabulary the place we do our work. We can still access words in other vocabularies - there are simple mechanisms that we use.

#

vocab guessing

setvocab guessing

#

In our program the lines above give us a new vocabulary called “guessing” and set it to be the default. From this point on, all words, variables etc go into the “guessing” vocabulary in the dictionary. The console helps us a little here:

Prompt with a vocabulary!

When we change the vocabulary with ‘setvocab’, the current vocabulary is printed before the ‘>’ prompt. The only time that isn’t the case is when our set vocabulary is the default vocabulary. The default vocabulary actually has the name ‘_’ - deliberately chosen to be innocuous, but its important it has a way of addressing it so that the expression:

setvocab _

will reset the vocabulary in use to the default internal one.

When we type a word at the console, the system search is a little more sophisticated when vocabularies are involved. In the first place, the default vocabulary is searched for your word - giving your vocabulary precedence over all the others. If the word can’t be found, the default vocabulary is searched and the word found there is used. If it isn’t found, the search ends. However there are two other cases for accessing words. You can prefix your word with a vocabulary name:

<vocab>::<word>

for example:

guessing::pick

_::pick

In the first case above, the word pick is taken from the ‘guessing’ dictionary. In the second it is the built-in. Using this method we can control which words we want to use. When the prefix is applied, only the addressed vocabulary is used. The final case uses a wildcard:

*::pick

Which searches all vocabularies, but the default is searched first.

Vocabularies are an important aside, but we need to keep going with our example. The vocabulary we are using is the ‘guessing’ one and we’ll make use of the selectors is a bit.

variable range

100 range store

: pick random range fetch % 1+ ;

This last fragment creates a simple variable ‘range’. Then we put the number 100 on the stack, get the parameter address of the variable by using its name ‘range’ and execute store which puts the number 100 into the variable.

The word pick (which happens to overload the ‘pick’ that is defined in the builtin dictionary) chooses a random number. K4’s random number generator picks a number between 0 and 2^32 or 2^64 (depending on which installation of K4 you use). That’s too large a number to guess. The simple mathematical trick done is to take the ‘modulus’ of that random number by our range. Modulus is the remainder after division by our range and will be mathematically between 0 and range-1. Our user is thinking of 1 to range so we politely add one and provide that as the output of pick.

The next word ‘inrange’ tests if the number on the top of the stack is between 1 and range (inclusive):

: inrange dup 0 > swap range load 1 + < and ;

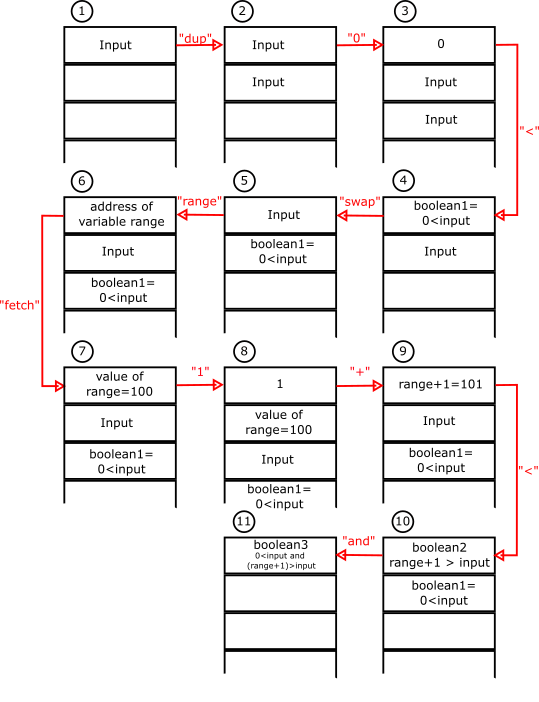

The diagram below shows the stack contents for each word executed by the “inrange” word (depicted in red). You can follow steps 1 through to 11 and see how each word effects the stack:

Stack operations for the “inrange” word.

The word starts with an input value on the stack, and by step 11 this has become a boolean (true/false) value that is true when that input is inside the required range.

Now we can construct a word that asks the user for their guess:

: ask

begin

." Pick a number between 1 and: " .

range @ . \? emit space flush

input

$> stoi

(* true/false on tos, value one below *)

2 _::pick

(* duplicate value below to tos *)

inrange and

until

;

This word uses a begin-until loop that continues until the user has typed a number and it is in range. We’ll break it down:

: ask

begin

This defines the word ‘ask’ and marks the beginning of our until loop

." Pick a number between 1 and: " .

range fetch . \? emit space flush

This creates a string “Pick a number between 1 and: “ and prints it. Then we load the value of range and print it. We finish by printing a ‘?’ and a space. The word flush is required here because there is no end-of-line in our output and we must force the operating system to print what it has without waiting for one.

input

$> stoi

(* true/false on tos, value one below *)

The word input above gets a string typed by the user. We need to convert that to an integer. However the user might not be co-operative and types something that isn’t a number. Our word ‘stoi’ pushes two values onto the stack. The first is the integer value (or zero if one can’t be parsed) and the second (on top) is a boolean that will be true if the string was a number. We have to do some stack trickery to complete our input checks now:

2 _::pick

(* duplicate value below to tos *)

inrange and

Firstly we need to recall our vocabulary discussion above. The expression ‘_::pick’ tells us to use the definition of ‘pick’ found in the default dictionary, not the one we have defined for this program - that wouldn’t do what we want. This is some of the power of multiple vocabularies.

Secondly, we use the built-in pick as illustrated below to get a copy the value from ‘stoi’ onto the top of the stack.

“pick”

The nth value (2 in this example) is duplicated to the top of the stack

(Using the stack diagram above, Y is the value from stoi, and X is the boolean that stoi has used to report the validity of that value. Z is arbitrary).

The word ‘inrange’ is now invoked using the value Y. Use your minds-eye to recognize that we have a boolean pushed by ‘inrange’ and the boolean ‘X’ from ‘stoi’ that says the number was valid. Two booleans on top of the stack and then we invoke the word ‘and’. In the boolean world the ‘and’ operator on two inputs only gives a true output if both inputs are true. So after ‘and’-ing, we will only have true on the stack if the number was valid and the number was in range. So finally we hit:

until

This word evaluates th top of stack and if that is the ‘true’ value, execution continues (in our case ‘ask’ exits and the value ‘Y’ is left on the stack. If the top of stack were false, until will jump back to the begin and the user will be asked again - until they give a valid answer.

So now we can play our game:

variable guesses

variable trying

variable secret

: play

0 guesses store

pick secret store

begin

clear

ask trying store

guesses fetch 1 + guesses store

trying fetch secret fetch < if

." Your guess is too low!" .r

then

trying fetch secret fetch > if

." Your guess is too high!" .r

then

trying fetch secret fetch = dup if

." You got it in: " . guesses fetch .

." \ guesses! Well done" .r

then

until

;

Three variables hold the number of guesses, the value we are trying and the value we are keeping secret. The word ‘play’ starts by initializing guesses to zero, picking a random number in our range (using our definition of ‘pick’) and storing it in the ‘secret’ variable. Then we start a begin-until loop.

Firstly we ensure the stack is empty. We shouldn’t let things build up there! Then we ‘ask’ the user for a number an save it in ‘trying’ (trying store). We also increment the value of ‘guesses’ by one each time we come around this loop.

Then we have three ‘if’ statements. The first compares ‘trying’ to the ‘secret’ and determines if the guess is too low. The second does the converse to see if it is too high. The last tests for equality. In doing the test it uses ‘dup’ to leave true/false on the stack after the ‘if’. (Note that the tests ‘<‘, ‘>’ and ‘=’ consume the top of stack). We congratulate the player.

Having left a true/false value on the stack from the ‘=’ comparison, the ‘until’ word will loop back to begin if the user was wrong and exit if they were right.

And there you have it. Tons of detail and a real K4 guessing game. Enjoy!